“We’ve been called powder-puff racers and lady birds, and perhaps even lady bugs, but no matter what they call us, you’ll note that the girls and women handle their ships just as competently as the male aviators.”

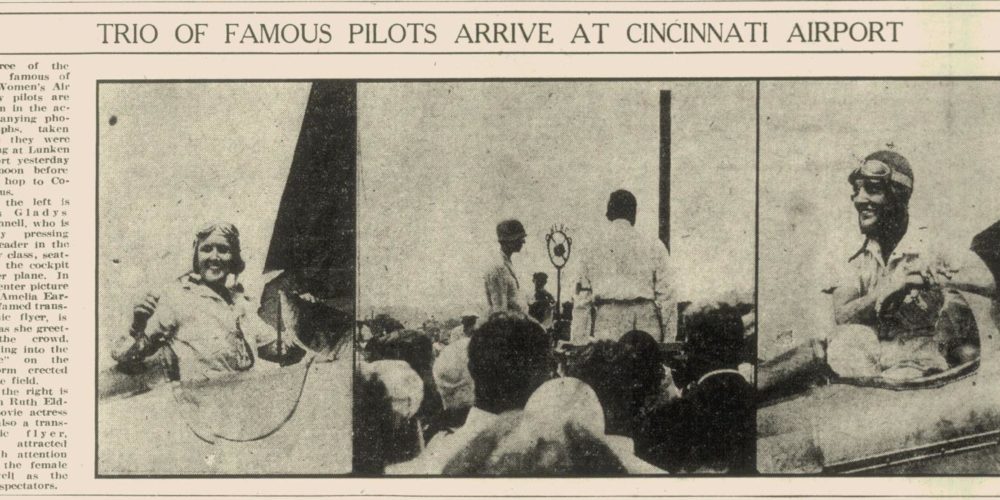

That was Amelia Earhart’s message to reporters and 15,000 spectators as she stepped out of her Lockheed Vega, landing at Lunken Field in Cincinnati, Ohio, on Aug. 25, 1929.

Earhart was making a scheduled landing, not an unexpected stop as some of her competitors in the Women’s Air Derby had been forced to make, setting down in a cow pasture due to sand in the engine, heavy fog, or possibly, sabotage. At the last minute, Cincinnati was added to the competition’s 11 required check-in points, giving the women the opportunity for rest, repair and photo ops.

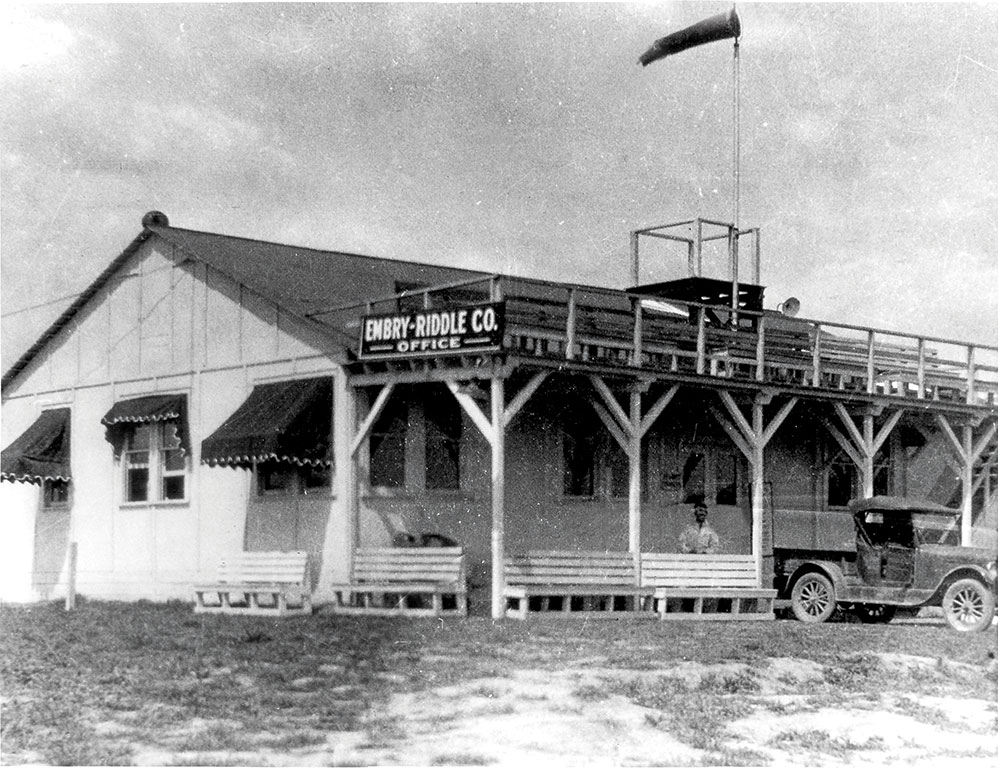

The fliers were guests of the Embry-Riddle Company. With the backing of the Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce, T. Higbee Embry and John Paul Riddle negotiated with the National Air Races to replace Indianapolis as the next-to-last stopover before the eight-day derby culminated in Cleveland. On Aug. 13, Ohio newspapers announced the fliers would spend four hours at Lunken Airport.

The Women’s Air Derby was the first official women-only race in the U.S. It drew 19 participants flying from Santa Monica, California, to Cleveland. Like their male counterparts competing in the National Air Races, the pilots were required to have 100 hours of solo flight and a minimum of 25 hours of cross-country flying. Fourteen flew heavy-class airplanes, and six flew lighter-class airplanes. They competed for prizes totaling $8,000.

Although some, like humorist Will Rogers, trivialized the event, calling it the Powder-Puff Derby flown by “petticoat pilots,” it proved dangerous to several fliers and fatal to one. Marvel Crosson crashed and died in the Arizona desert. Despite public outcry, the remaining fliers continued as a tribute to her. Pancho Barnes wandered into Mexico and crashed. Ruth Nichols crashed. Frances Noyes battled an in-flight fire. Earhart had electrical problems. Claire Fahey withdrew from the race when she believed someone deliberately damaged her wing wires with acid.

Fourteen women made it to Cincinnati to take advantage of Embry-Riddle’s ground support and hospitality. The company provided mechanics and free gas and oil and kept the field clear of over-excited spectators who wanted to get too close to the aircraft. Embry was the event’s official referee and in this capacity, disqualified one contestant who lost her way to Cincinnati and skipped the required check-in. Riddle served as chief starter, and he and operations manager, Stanley C. “Jiggs” Huffman, were both judges. (The next year, Huffman would break the light airplane solo endurance record, flying over Lunken for more than 26 hours.)

Thanks to the company’s new public address system, the crowds heard directly from Earhart, Barnes, Thea Rasche, Blanche Noyes and the famous flying Ruths — Elder and Nichols. Elder shouted “Whoopee” upon finding out she was the eighth to land and the crowd roared. They also cheered lesser-known hopefuls Mary Haizlip, Jessie Miller, Opal Kunz, Mary von Mach, Gladys O’Donnell, Margaret Perry, Neva Paris and Vera Dawn Walker. Bobbi Trout and Edith Foltz had been disqualified earlier in the race.

At the home of Riddle and his wife, Grace, the women dined on a buffet of “chicken a la strut, radiant-cooled iced tea and angel-wing cake,” according to a local newspaper.

During the stopover, they compared notes on engine performance and checked maps. Earhart tended to a wicked sunburn, and Rasche soothed an upset stomach with bottles of milk. When the engine of her Travel Air died upon landing, she explained to reporters, “When the tummy of my plane is sick, then my tummy is in trouble, too.” The German pilot worked alongside Embry-Riddle mechanics until the Wright J-5 engine was humming.

Phoebe Omlie, a certified airplane mechanic and the first female certified transport pilot, won the light class, flying a Monocoupe 90. Louise Thaden, flying a Travel Air J-5, won the heavy class. At 25, Thaden became the first female pilot certified in Ohio. With just a year of experience, she had already set altitude, endurance and speed records in light planes. She was one of three derby competitors to co-found the Ninety-Nines. In 1991, NASA astronaut Eileen Collins carried Thaden’s cloth flying helmet, autographed by the other racers, into space to honor her.

Hosting the derby was a publicity coup for Embry-Riddle, which tapped into the excitement about the race to announce its new air service to Cleveland. The company also recognized another potential market. A 1929 ad for Embry-Riddle Flight School promises, “Women will learn to fly to keep pace with progress, to express their new freedom, and now for the sport of it.”

Editor’s Note: The information and quotations included in this story came from articles that were originally published in the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune from Aug. 13-26, 1929. Kim Sheeter is a member of the Eagle Writers Corps and an executive communications specialist at Embry-Riddle. She publishes the aviation / “prop culture” website WilderBlue.com and is at work on a biography of John Paul Riddle.