Inside a yellowing envelope from Riddle-McKay Aero College is a typewritten page — a form, really— that matter-of-factly certifies the flight time of Frederick J. Brittain (’43). He accumulated 2,428 hours piloting PT-17 Stearmans and AT-6 Texans at the No. 5 British Flying Training School (BFTS).

The certificate hints at a rich story: “Mr. Brittain has never been involved in an aircraft accident at Riddle Field. He has flown more hours in Riddle Field aircraft than any other pilot at Riddle Field,” noted an apparently impressed R. V. Walker, the operations and engineering officer at the school in Clewiston, Florida.

A Living Archive

Victoria Brittain, Frederick’s daughter, unloaded six boxes of that story in May 2019 at the Embry-Riddle archives in Daytona Beach, Florida. The photos, personal letters and flight logs recording nearly 30,000 hours document her late-father’s life and career in the skies.

“It’s very uncommon that someone has that much material, and it’s that well organized,” says Archivist Kevin Montgomery. “Especially when it’s all about one particular person. That always adds color to the Embry-Riddle story.”

Frederick, who descended from a family of actors and scenic artists, specialized in color.

On the back cover of his first flight log are cryptic diary entries — dated one-liners under the heading, “Things I think of.” They mark his first glider flights — which became a lifelong passion — a Christmas Day road trip to perform snap rolls, and one on New Year’s Day 1942, less than a month after the attack on Pearl Harbor: “A new year, a new WAR. What can you use a pilot for?”

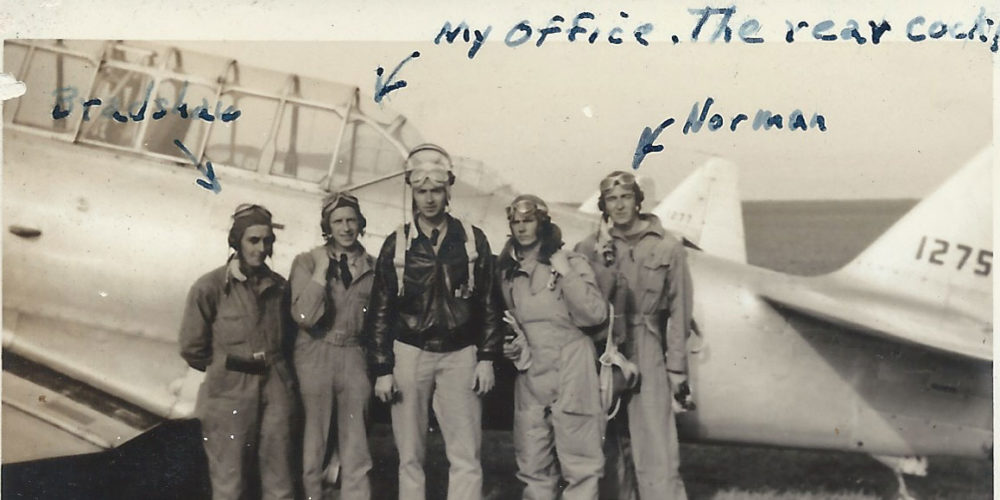

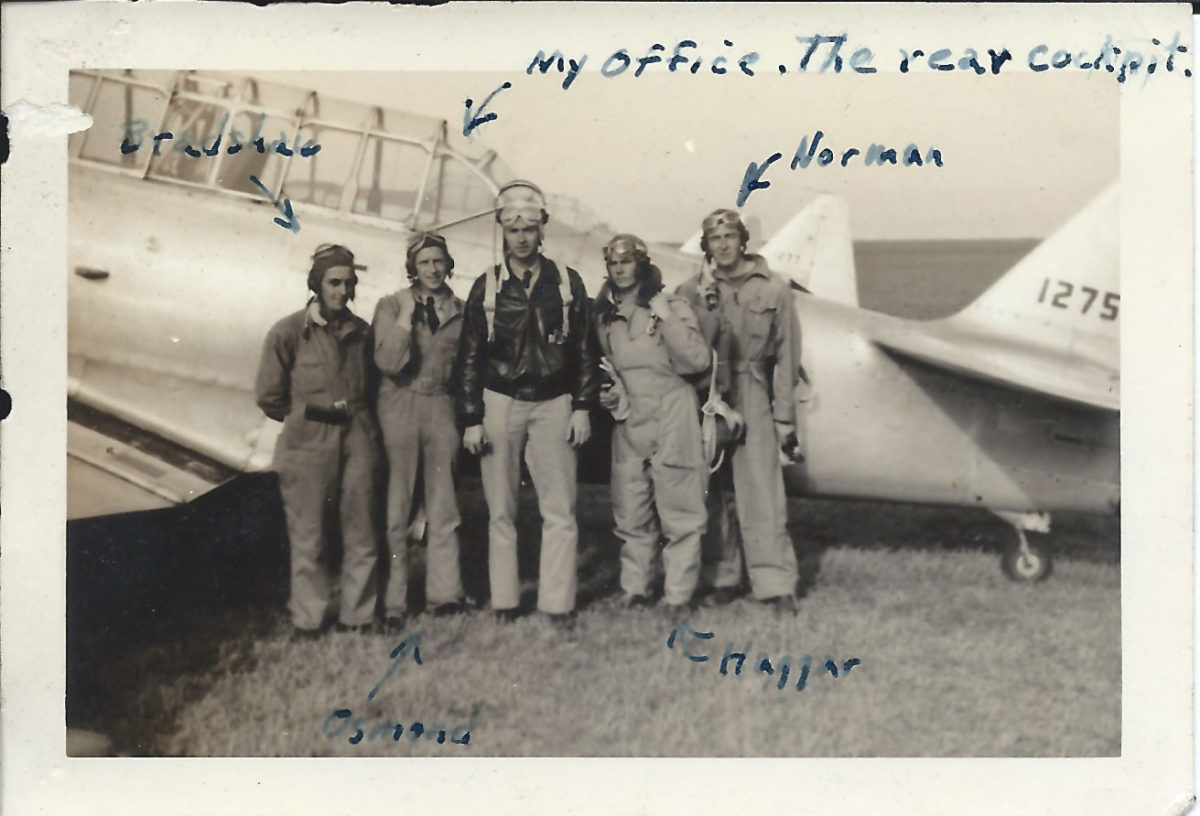

Exactly one year later, Frederick had completed a refresher course at Riddle Field and on Jan. 3, 1943, he started instructing British cadets for the Royal Air Force (RAF). Operated by the Riddle-McKay Aero College, one of six divisions of then-Riddle Aeronautical Institute, No. 5 BFTS trained 1,800 RAF cadets from 1941 to 1945.

Frederick’s acumen as an instructor and his personality earned him lasting friendships. Victoria’s collection is dotted with letters and Christmas cards from her father’s former British trainees, most of whom were bomber pilots.

“It rather shook me flying over the English country side for the first time,” Sgt. C.L. Norman wrote in July 1944. “I was glad that I paid attention to the navigation while I was at Riddle Field. It doesn’t do very much good here, to fly the ‘iron compass’ (railways).”

Norman continued: “I must thank you again for the great trouble you took to get me ‘on the ball.’ I did so much enjoy my training with you, I only wish I could come over to Florida, [and] go through advanced again. All of us here long to get hold of an AT again, [and] do some real flying in decent weather, but I think we have all seen the last of the good old Texan.”

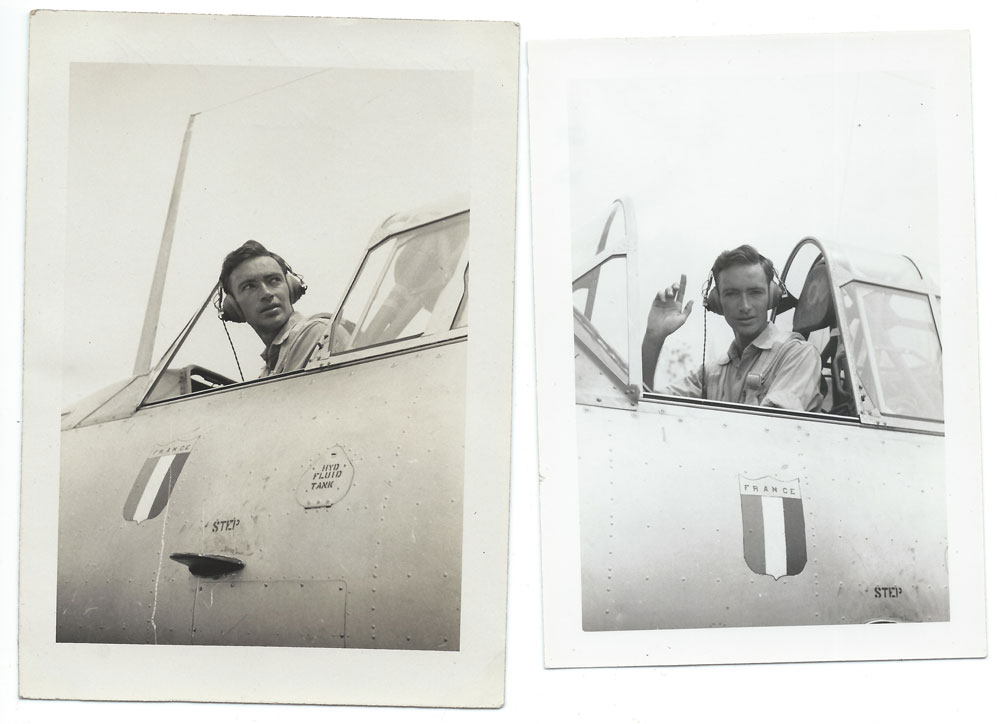

French Connection

When World War II ended, Riddle Field closed. In search of revenue, the Embry-Riddle Company in Miami picked up a contract to provide basic and advanced flight training to French Navy pilots in Homestead, Florida. Frederick flew to Homestead to train the Frenchmen. He then moved on to piloting flying boats for commercial airlines: Skyways International and British Guiana Airways.

Frederick returned to Miami in 1950, to follow John Paul Riddle in his new business, Riddle Airlines. “Mr. John Paul Riddle was president during the early years and was a wonderful friend,” he wrote in a retrospective resume.

Air Ways

Frederick was a captain at Riddle Airlines for 28 years, through the company’s name change to Airlift International (1963) and its acquisition of Slick Airways (1966). During that time, he fathered Victoria and her sister, Jacqueline. The family would often fly to meet him to spend time together between routes, Victoria says.

But his down time away from work was often spent in the sky. “When he wasn’t flying, he was flying,” Victoria says. “Mainly gliders. We took one trip — there was some soaring contest — and he soared all the way to Las Vegas. My mother [Alicia] took us in the car and we followed him all the way out, and wherever he landed was where we stayed.”

Frederick’s love of flight was passed down to his younger daughter. “He pinned my wings on me,” Victoria says, who got her glider and private pilot certificates from her dad. “When I went to work at NASA at Cape Canaveral, I joined the aero club at Patrick Air Force Base. I made him join as an instructor so I could have, in my view, the best instructor.”

Though Frederick didn’t have a formal education past high school and flight training, Victoria — a military aviator herself — once described him as, “the most proficient and educated aviator and engineer that I know. He is an aviation artist. … When he teaches, he imparts this artistry on the students.”

But for all her admiration, Victoria does surpass her father – just. “I did get one on him,” she says with a smile and a chuckle, revealing a fact that she ribbed her dad about. “I got rotary wing.”

Editor’s Note: Frederick passed away in 2002. Victoria is preserving her father’s memory at frederickjbrittain.com. She plans to donate this collection to the Embry-Riddle Archives.