A man charged in a crime went missing. Police in Iowa had spent hours searching — knowing that a firearm was also missing from the suspect’s home — when Deputy Jason Grubbs (’00) put a drone in the air and found the man’s car within minutes.

He maneuvered it into position to look in the driver’s window and found that the man had taken his own life. He informed other deputies immediately, which allowed all searchers to leave the area ahead of incoming bad weather. “There were so many times prior to us having these aircraft that I thought, ‘We could really use one,’” Grubbs said.

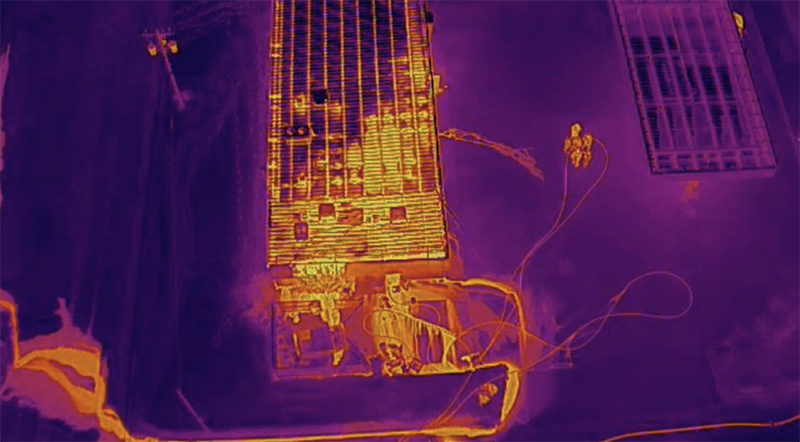

In the almost two years since his department has gone live with an uncrewed aircraft systems program, the aircraft have been used to find missing children, inspect the aftermath of natural disasters, have eyes on search-and-rescue divers in swift water, clear buildings, look for toxic spills and identify hot spots in an arson fire.

The Story County Sheriff’s Office in Nevada, Iowa, including Grubbs’ team, provides law enforcement services for 10 different communities and will respond when called upon by federal and state agencies.

“To be able to risk equipment instead of human lives I think is one of the biggest aspects of this,” he said. “You can replace the equipment obviously.” They can also get there faster. When a child with special needs is missing, every second matters.

Grubbs is a U.S. Air Force veteran – seven years active duty, seven years as a reservist – who completed Embry-Riddle’s bachelor’s degree in professional aeronautics. He always wanted to be a police officer and has an associate’s degree in law enforcement. And he’s skilled at both. In 2003, he was selected for the General Daniel “Chappie” James Jr. Award of Merit at Air Force Officer Training School and in 2019 was named the Iowa American Legion Police Officer of the Year.

“UAS are going to be standard law enforcement equipment at some time in the future.”

— Jason Grubbs (’00)

As team leader, he directs 13 people who hold FAA Part 107 remote pilot certifications and a fleet of 10 aircraft ranging from small units that can go into homes ahead of officers serving warrants and larger aircraft that can see for miles across dense cornfields and rooftops, capturing crystal–clear video. Their program won first place in the public safety mission excellence category in the Association for Uncrewed Vehicles International Xcellence Awards.

In 2013, the U.S. Department of Justice estimated that fewer than 0.5 percent of police departments in the U.S. had UAS technology. According to open-source estimates by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, more than a thousand departments have access to a drone, but that estimate is likely undercounted.

The technology is advancing rapidly with newer models and cameras available. But it’s not perfect.

And it’s not a space that was designed for law enforcement, Grubbs notes. There was no manual on clearing a house his first time guiding a drone through a doorway – a delicate maneuver in a closed space – and it hit the door jamb and crashed.

He and his team have learned that when the aircraft is flying over cornfields in the middle of a 90-degree day, the high infrared energy level of the corn distorts the camera’s image, making it difficult to locate a person in the field. So they try to go with the direction of the rows and methodically cover the field. FAA rules have eased somewhat in the last few years, and there’s now a Law Enforcement Assistance Program that provides guidance to agencies regarding federal regulations.

Two years in, he’s sharing what he’s learned, training law enforcement and offering advice through a program at Kansas State University.

“It’s just almost in every sector right now,” Grubbs said of drones. “If you’re not getting involved with it at a public agency, I think you’re going to be behind the power curve.”

“UAS are going to be standard law enforcement equipment at some time in the future.”