Rising sea levels, warmer temperatures and increased human activity are taking a toll on Florida’s coastal ecosystems. Intent upon safeguarding this delicate habitat, Embry-Riddle students and professors are using unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) to collect critical data on the changing coastal environment.

“It’s important, because our climate is changing,” says Dan Macchiarella, a professor of aeronautical science at Embry-Riddle.

In collaboration with the University of Central Florida’s (UCF) National Center for Integrated Coastal Research, a group of students used UAS to survey oyster reefs in the Indian River Lagoon system on the east coast of Central Florida in 2019. The project is now expanding to investigate the potential for dead reefs to be used as nesting sites for threatened birds, including the American oystercatcher and least terns.

“Collaboration started organically — the best way,” says Linda Walters, a biology professor at UCF. “Embry-Riddle and UCF coastal scientists met and realized we could help each other better understand and hopefully help improve the Indian River Lagoon and associated biodiversity.”

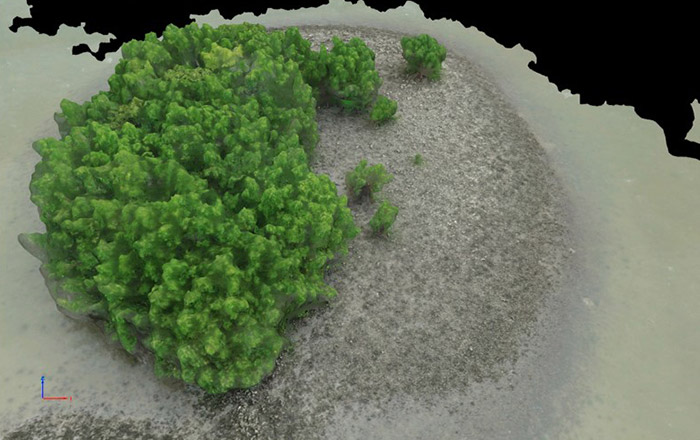

UAS are flown over the oyster reefs at low tide, taking photos that are stitched together to make high-quality images that are about 25 times more detailed than Google Earth’s, Macchiarella says. The UAS images create a baseline of data that can be used to measure the changes in an area. The next step is to use lidar — a remote sensing method that uses laser light to measure distance — to make digital 3D representations of the survey site.

“Lidar also gives us the ability to penetrate vegetation and mangroves, which grow a lot around oyster reefs,” Macchiarella says. “They share the same habitat.”

create 3D models of the oyster beds.

UAS: Tools for Conservation

To further their research, the Embry-Riddle-UCF team is applying for a state grant to conduct a topographical analysis of wading bird nesting sites for habitat protection. As increased coastal development and human activity have reduced the beach areas where wading birds have traditionally nested, some birds are now nesting on dead oyster reefs.

“Their habitats have been disturbed by development,” Macchiarella says. “Where they traditionally go is not as viable.”

The research will look at elevation, among other metrics, in site selection for nesting. The findings could help guide future restoration and conservation efforts in the Indian River Lagoon.

The researchers agree that UAS, which can easily collect data in hard-to-reach areas, are ideal tools for environmental research projects.

“I’m interested in testing this technology for understanding many important human impacts — one being quantifying the number and level of damage by boat strikes to oyster reefs, shorelines and seagrass beds in the Indian River Lagoon, and to see if we could use drones to count oysters on a reef — to minimize field efforts in the future,” Walters says.