It’s almost 6 a.m. (MST) on Dec. 22, 2019. A bank of spotlights focuses on the pre-dawn sky above the desert at White Sands Space Harbor, New Mexico. Minutes later, a spacecraft recovery team — and the world via NASA TV live — witness a first-of-its-kind engineering feat. Suspended by three parachutes and surrounded by six specially-designed airbags, the Boeing Crew Space Transportation-100 Starliner spacecraft descends gently to the Earth’s surface.

Among those celebrating the landmark moment were more than a dozen Embry-Riddle alumni who work for the Starliner program. [See sidebar]

“We’re the first fully reusable (human-rated) capsule to land on land,” said Louis Atchison (’02, ’04), chief of launch and recovery operations for Starliner.

Proving the ground-landing capability of the spacecraft is a critical step to advancing Boeing’s business model for Starliner, Atchison said in an early-December phone interview. “The reusability of the vehicle helps us give the customer the best value on this particular capsule platform.”

Starliner’s nominal landing was the highlight of its inaugural Orbital Flight Test (OFT). “The hardest parts of this Orbital Flight Test were successful,” said NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine in a statement released after Starliner’s successful touchdown. Bridenstine also acknowledged the need to investigate two software errors and an intermittent communications link issue that occurred during the test flight. An independent Boeing/NASA investigation took place, and Boeing is addressing the recommended fixes, according to a public statement on March 6.

Eagle Team

Together with Atchison, at least 14 Embry-Riddle alumni and one student have touched nearly every aspect of the historic spacecraft’s development. This Eagle team includes electrical, materials, manufacturing and production engineers, a materials management lead, a systems test conductor, assembly and aerospace technicians, a welding shop lead/crane operator and a safety specialist.

Largely working behind the scenes, Kimberly Fuentes-Lehtonen (’17), an occupational health and safety specialist for the Starliner program, has helped ensure workplace safety for her Starliner teammates since January 2018.

The most common safety hazards — like at any construction site — relate to “slips, trips and falls,” she said in an early-December interview. “You’d be surprised how many areas have to be reached when working on [Starliner].”

Still, job-site mishaps have been rare to none, she said. “Space is a very safe industry, because it has to be,” Fuentes-Lehtonen explained. She helps keep it that way by listening to employees, mitigating safety hazards and conducting safety training. “I’ve trained technicians to NASA engineers to astronauts,” she said. “To be a part of this program is so unique. We’ve never built a capsule like this before.”

Orchestrating the Launch

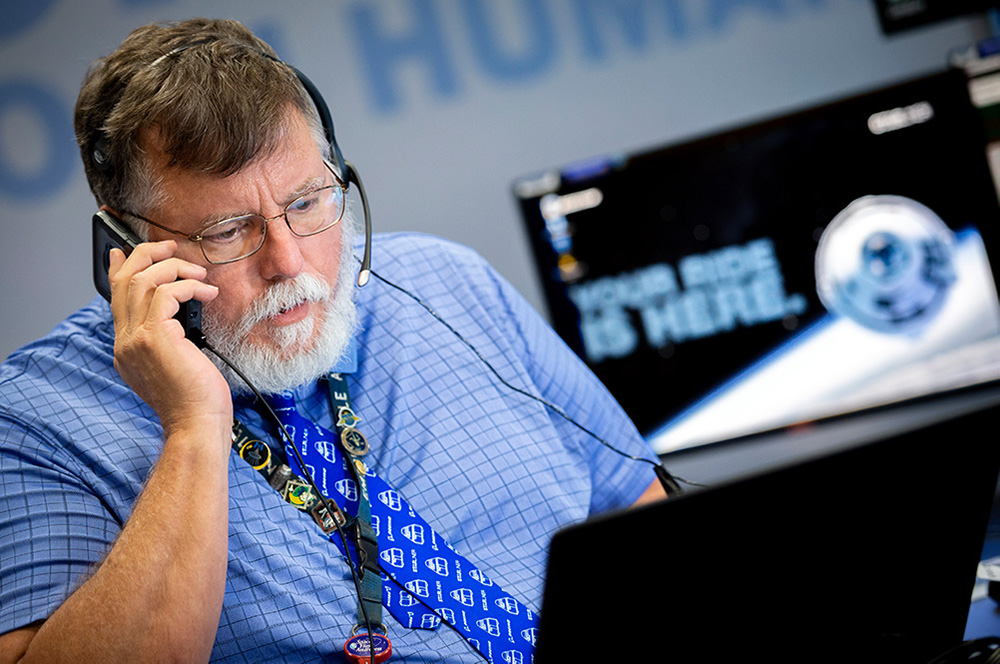

The conductor of the launch-day countdown, Atchison earned a B.S. and M.S. in Engineering Physics from Embry-Riddle. After eight years with Boeing’s satellite division, he was originally brought on to the Commercial Crew Program as a flight test director. Five years ago Atchison was asked to create Starliner’s launch architecture. The plan coordinates multiple teams and activities to operate in lockstep, so the heritage Atlas V rocket system marries up seamlessly with Starliner for a successful liftoff, he said. “It’s been a very interesting journey integrating all of the pieces of this puzzle.”

Maturing the concept of a ground landing for the reusable capsule was another of Atchison’s challenges. “The [space] shuttle landed on a runway. … This is an off-road, expedition-type spacecraft recovery,” he explained.

Starliner’s landing isn’t the only thing that makes it distinct from the Space Shuttle and NASA’s previous capsule programs, Gemini and Apollo. “It’s a lot like comparing a 1955 Corvette to a 2020 Vette or a 1975 Cessna to a 2019 Cessna. The avionics, the fit, the finish, the feel — everything is completely different [from Gemini and Apollo],” Atchison said. “The challenge with Starliner is that most of what we’re doing is new.”

Discovery Is Part of Development

“We have a custom, one-of-a-kind, hand-built spacecraft,” affirmed Gary Wedekind (‘81, ’83, ’91, ’92).

With more than 37 years of experience, including multiple roles within the Boeing Starliner Program as an integration engineer, manufacturing engineer, test engineer, test conductor, test director and Boeing mission support room manager for test flights, Wedekind is intimately familiar with crew and service module designs and as-built configurations.

“The primary goal of the OFT is to perform on-orbit testing and performance checks for systems that cannot be tested on the ground, and to understand all the successes and any problems that occur,” Wedekind said in a phone interview prior to Starliner’s Dec. 20 launch.

“Sometimes standalone hardware will pass qualification and is integrated onto the vehicle; now that box has to respond correctly with other boxes and other systems, and you realize it doesn’t play well with others. It’s based on these unplanned discoveries that you now work to resolve them so they don’t occur again,” Wedekind said.

“The most important thing is we get it right for the people who will fly our spacecraft.”

Editor’s Note: Boeing and SpaceX were selected by NASA in 2014 to develop capsules to transport astronauts to the ISS. Since the Space Shuttle program retired in 2011, American astronauts have traveled to space aboard Russian Soyuz rockets.