In 2009, two physicians working aboard the International Space Station for six months were reading research procedures. And at some point, it became harder to read the words on the page.

Astronauts Dr. Michael Barratt and Dr. Bob Thirsk tried slightly stronger lenses, and their immediate problem was solved. But their discovery led to NASA researchers uncovering that nearly 70% of astronauts to that point showed at least one symptom of what is now known as Spaceflight Associated Neuro-ocular Syndrome, which leads to swelling in the optic disc and flattening of the eye’s shape, resulting in declining vision.

That’s what the Human Research Program at NASA Johnson Space Center does: Investigate human health in space and develop solutions to protect astronauts. Nichole “Nikki” Schwanbeck (’97) manages the implementation of all NASA human research in space as Deputy Manager for Flight in NASA’s Human Research Program Research Operations and Integration element.

Schwanbeck will be managing the implementation of a study this year that will include testing countermeasures to combat the vision decline in astronauts. She also understands this particular study from a personal perspective.

“That actually happened to me when I was pregnant with my kids,” she says. “I had LASIK surgery before I had kids. And then, because of the fluid retention with each child that I had, my eyesight just got worse and worse, and it never returned back to normal because of that fluid retention, which is similar to the fluid shift into the head that astronauts experience when they get to space. So it made me want to understand why that happened.”

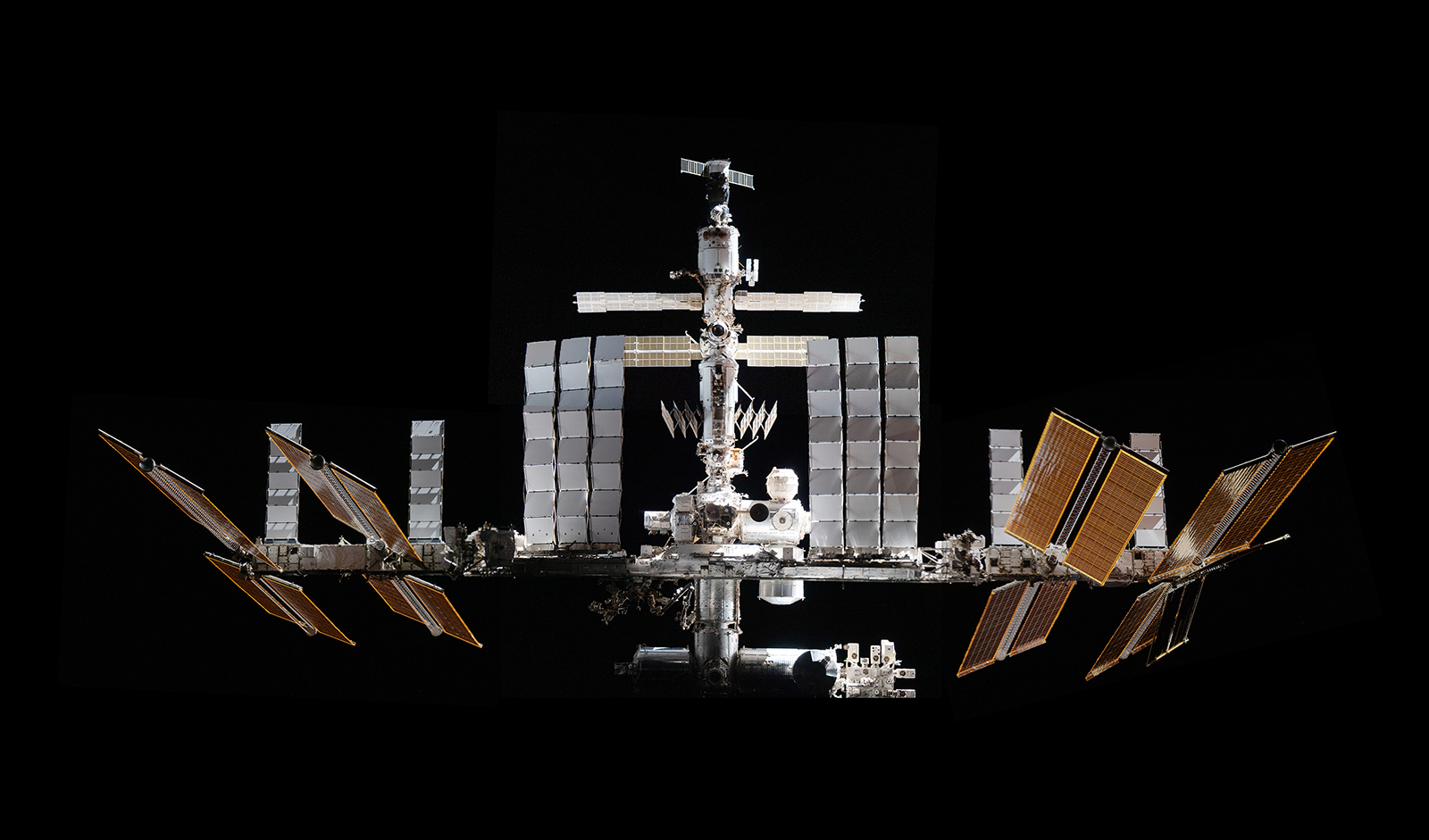

Six-month missions on the ISS has brought about advances in knowledge about how humans change when living in microgravity. But it was astronaut Scott Kelly’s one-year mission on the ISS that changed the scope of learning about how humans would fare on lengthy deep-space missions. Schwanbeck worked on the development of the human research studies for Scott, including the Twins Study with his twin back on Earth, retired astronaut and U.S. senator, Mark Kelly.

“We know these missions to Mars are going to take up to three years for transit, for surface operations and return,” she says. “So we want to see how it’s going to affect the human body.”

Schwanbeck is the project manager on the Human Research Program’s biggest study ever undertaken – and the longest. This next leap forward is the CIPHER (Complement of Integrated Protocols for Human Exploration Research) studies on the International Space Station.

“We know these missions to Mars are going to take up to three years for transit, for surface operations and return,” she says. “So we want to see how it’s going to affect the human body.”

— Nichole “Nikki” Schwanbeck (’97)

Consisting of 14 studies, the CIPHER project will be the most expansive effort to learn more about how human bodies behave in space and will be long-term — starting nine months before astronauts leave Earth and ending three years after they re-enter the atmosphere. The first human subject is scheduled to launch this spring. Areas of study include cardio and vision, bone and joint, muscle physiology and egress fitness, vestibular system, and cognition and behavioral health.

“There’s just a lot of different studies that we’re trying to implement now,” she says. “Not all of them were derived from that one-year mission, but some of them were. We don’t have a full picture of what happens to the human body in long-duration space missions, which is one of the reasons that we’re doing CIPHER to try to get that full picture.”

Schwanbeck, who graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Engineering Physics and was a student-athlete with the volleyball team at Embry-Riddle, had a job out of college with NASA contractor United Space Alliance training astronauts and flight controllers on space station thermal control and electrical power systems.

“This was before a space station was even on orbit; nothing had launched yet. And so when I started, basically the first six months on the job was me and all the other new hires going to what they called the training academy, where you learn everything about the space station.”

In 2006, she became a civil servant with NASA where she continued to train people before advancing through the Human Research Program ranks to leading the implementation of human research studies in space.

But sometimes, she’s the subject. She’s volunteered for several studies at Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. She’s flown on a zero-G flight to test a vein press that measures venous pressure non-invasively, which is being used on one of the studies on ISS now. And she’s evaluated a blood pressure cuff on her leg, testing to see if this could be a viable option to counteract astronaut vision changes.

This experiment is expected to make it to space this year.

“I also go and I taste astronaut food that they’re developing for astronauts to eat and give them feedback on texture and taste and smell and appearance and things like that,” she says.

“You’re helping the researchers in doing these tasks that my group will then help them change into ‘How can we do this on the space station in zero gravity?’ or ‘How can we do this when the crew members land on the surface to test how quickly they recover from zero gravity to be able to perform surface operation tasks?”

It’s the chase of discovery that motivates her at her job. “It’s not boring. There’s something new every day. I like that, that it’s not something that’s routine.”

But when she needs a recharge, Schwanbeck, who is a member of the College of Engineering Philanthropy Council and a founding member of the Embry-Riddle Women’s Giving Circle, likes talking about her work in her children’s classrooms and with Embry-Riddle students.

“Just talking with them, even just a five-minute conversation and seeing their enthusiasm about space really resets my enthusiasm for it.”