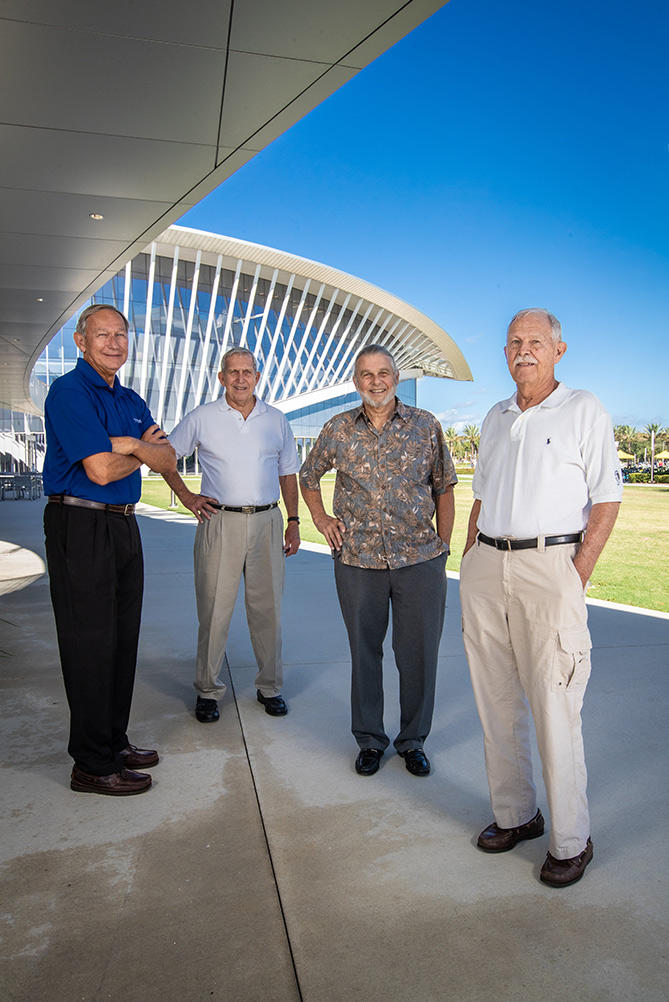

Gerald “Jerry” (’60, ‘66), Allen (’65), Calvin “Cal” (’70) and Norman (’73) Betz have more than their last name in common. Together, the brothers witnessed and contributed to over a decade of Embry-Riddle’s history, including its move from Miami to Daytona Beach and its transformation from a flight training/technical school to a fully accredited nonprofit university.

The family’s legacy at the university started in 1955 with the eldest brother, Jerry. “I was in an airplane (C-47) and I was reading a magazine, and in the corner was this little ad [for Embry-Riddle],” he recalls.

An airborne radio operator for the Air Force during the Korean War, Jerry started considering his post-war future. He filled out and mailed the enrollment form.

“I got the card back and it said, ‘Yeah, come on.’ They were looking for people; they were building the school,” Jerry says.

Following the conclusion of World War II, Embry-Riddle’s South Florida military flight and technical training operations — former income streams — dried up. The school turned its focus to commercial aviation and started actively soliciting veterans looking to retrain for civilian careers.

Jerry was one of the GIs who came. In 1958, he moved to Miami and started taking classes at Embry-Riddle’s Aviation Building.

“It was like a big hotel; everything was in there, travel agencies and other businesses; they just all had rooms in it,” Jerry says, describing the school’s unique setting.

Finding His Footing

Allen started his college education at Michigan Tech, but admitted he floundered there. He quit school and went to work as an engineering aide at Pratt and Whitney in West Palm Beach.

“After a couple of years, I got a feel for what the engineering field was like and the people in it — how smart they were, how smart they weren’t. And, I said, ‘I can do that.’”

By now, Jerry had completed an associate degree in aeronautical engineering and was working at the Martin Company (now Lockheed Martin) in Cape Canaveral.

“Jerry had gotten a job immediately out of [Embry-Riddle], so I ended up going there as well,” Allen says.

It was a time of transition. At the urging of Jack Hunt, then a consultant for Embry-Riddle, President Isabel McKay moved to reorganize the school as a nonprofit corporation. The new status would open doors for federal aid. A few years later, Hunt, now president, recommended the school consolidate its South Florida operations on one larger property that would allow for future growth. The board ultimately chose Daytona Beach as the school’s new home.

Operation Bootstrap

Allen was a student at the time (1965) and helped with the move, which became known as “Operation Bootstrap,” because of the human resolve and volunteer labor it took to accomplish.

“I disassembled some of the equipment down there and loaded up trucks. Then, I helped unload the trucks and reassemble some of the labs, wind tunnels and a lot of the lab equipment [in Daytona Beach],” says Allen, who shortly thereafter was elected president of the first Student Council.

Fly Boy

Enter Cal. “When I got out of high school [1964], I knew I wanted to fly,” he says. “My whole purpose in life was to get in the U.S. Air Force.”

After working and saving money for a year, Cal enrolled in the aeronautical engineering program at Embry-Riddle. “My dad thought all his sons were engineers,” he says. In 1966, when the school started offering a B.S. in Aeronautical Science, he promptly changed his major.

Cal and Allen, who had one trimester together (before Allen graduated), helped create the first intercollegiate sports field at Embry-Riddle.

Dean of Students Herbert Mansfield had started a men’s soccer team, Allen explains. “Cal and I were ordered by him to lay out a soccer field.”

Building an athletics program was part of the school’s greater goal of being accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS).

“[Mansfield’s] goal was to have the best soccer team in the region, and he did it. The teams he put together beat the University of Florida, Stetson, Rollins and Florida State,” Cal recalls.

Cal also helped the school develop its physical education (PE) course, another SACS requirement. “One day, I went into his [Mansfield’s] office and he said, ‘I don’t have time to teach this PE course anymore. I want you to teach it.’” Cal ended up getting paid for teaching and earning PE credit at the same time. “All we did was flag football,” he says.

Under the leadership of President Jack Hunt, in 1968-69 Embry-Riddle was accredited by SACS as a “special purpose institution.”

Last But Not Least

Norman arrived at Embry-Riddle in 1967. He brought with him two years of engineering education from Lawrence Technical College.

“I liked the small class environment [at Riddle],” he says. While he had a couple stops and starts at Embry-Riddle, Norman says there was a strong incentive to finish. “I had three brothers who all had their bachelor’s degrees; I wasn’t going to be left out,” he says.

Norman completed a B.S. in Aeronautical Engineering and went on to earn an M.S. in Engineering and Project Management from the University of South Florida.

The brothers all credit Embry-Riddle for their career success. Both Allen and Norman contributed to the development of high energy laser systems. Norman retired in 2008 from The Boeing Company and Allen retired in 2009 from Pratt and Whitney.

Jerry, who returned to Embry-Riddle in 1966 to earn a bachelor’s degree, worked for Chrysler at Cape Canaveral and contributed to NASA’s Apollo program. In 1969, he returned to Michigan to take over the family business, Imperial Plastics Inc. He sold the business in 1999 and retired in 2001.

A lieutenant colonel in the Air Force, Cal retired in 1994 after 24.5 years of service. His final assignment was Air Force representative to the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) Southern Region. He continued to work for several different companies on FAA telecommunications projects, retiring in 2014.

Coming ‘Home’

The Betz brothers returned to Embry-Riddle for the 2019 Homecoming Weekend. Today’s campus is nothing like the school they attended, but Allen says some things have not changed.

“This is the real deal. When you come to Riddle, you run into people who are trying to get some place.”