After losing his sight in one eye as a teen, Shinji Maeda (’05) thought his longtime dream of becoming a pilot was destroyed.

But when he completed a 42-day solo flight circumnavigating the world, he proved to himself and others that sometimes the impossible is possible.

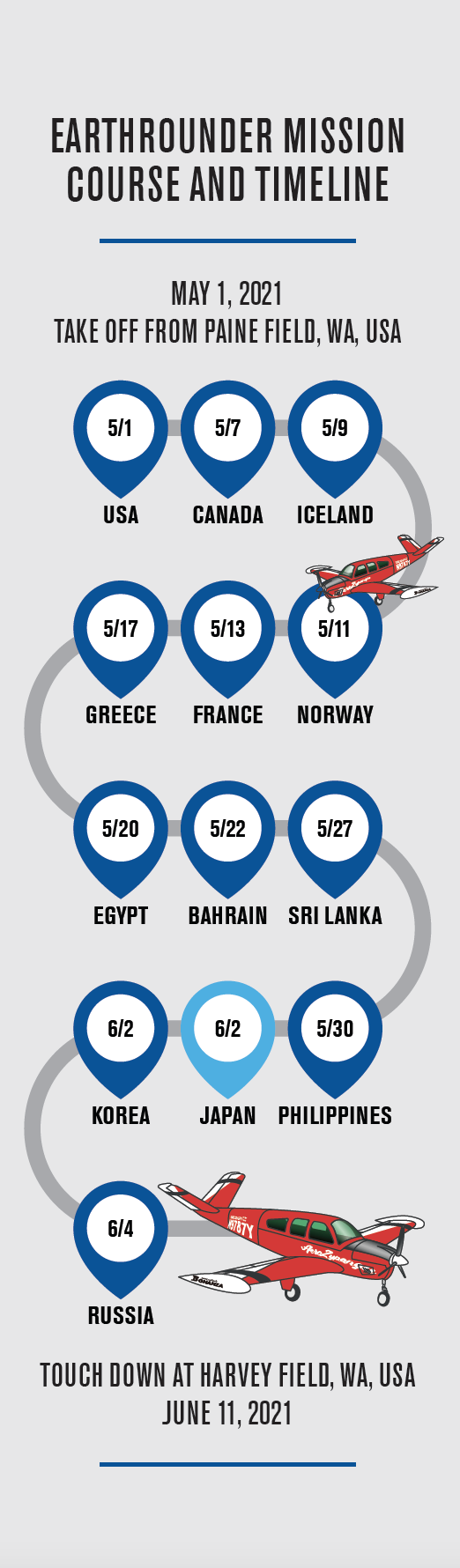

Taking off May 1, 2021, from Paine Field in Washington, he flew 22,000 miles and visited 18 countries in a 1963 Beechcraft Bonanza that he named “Lucy,” before landing at Harvey Field in Snohomish, Washington, on June 11.

“This flight pushed my limit beyond any life experience,” Maeda says. “The experience was just amazing, and the reason why I was able to get a pilot’s license was Embry-Riddle.”

Making his Earthrounder Mission wasn’t easy. He had to take leave from his full-time job as a manufacturing and operations analyst at The Boeing Company — and his wife, Makiko, and children, Tsubasa, 4, and Sana, 1.

“Luckily, my wife is very understanding,” he says. Along the voyage, Maeda encountered everything from sandstorms and icing to bureaucratic red tape.

“There was no space to make a mistake, which was stressful,” he says. “In fact, on a couple occasions, I felt like, ‘This is it. I don’t think I can make it.’”

The coronavirus pandemic threw additional challenges in his path.

“I had to be at airports at certain times when they were open due to pandemic, so I tried to push on to the next destination to get fuel,” says Maeda, 41. “I became the first COVID-19 vaccinated solo pilot around the world.”

The journey, which took years of planning, is key to his Aero Zypangu Project, a nonprofit he founded in 2015 that aims to encourage others to overcome challenges in their lives.

“I just want to pay forward what I got through aviation,” he says.

Early Interest in Aviation

Growing up on the Japanese island of Hokkaido, Maeda lived near a government flight school and would watch the trainees flying Bonanza planes overhead. He flew to Tokyo with his grandparents when he was around 5 years old and became even more fascinated with flight.

“When I saw my countryside from the airplane, I was just amazed,” he says. “It was a strong impression that set me on a path to become a pilot.”

After graduating from an aviation high school and enrolling to study aerospace engineering at a university, his life was turned upside down when he was 18 years old. He was critically injured after being hit at an intersection while riding his motorcycle. He survived, but his optic nerve was badly damaged, and he lost his sight in one eye.

“That was a devastating situation,” Maeda says. “Losing my eyesight was very bad for my career,

and I was deemed handicapped in Japan. I thought it was the end of my life.”

Flying at Embry‑Riddle

At Embry-Riddle’s Prescott Campus, Maeda found new hope that he may still be able to fly. Aviation safety professor Ed Wischmeyer encouraged Maeda to get more information and referred him to another person he knew who was able to fly with vision in one eye.

“Wischmeyer told me, ‘Being one-eyed is not a good enough excuse to not become a pilot. You can be a pilot,’” Maeda recalled. “At first, I thought my English was an issue, and I didn’t understand him right.”

But Wischmeyer took Maeda to the airport one day, where he owned a bright yellow Cessna, and told him to push the plane out and sit in the left seat.

“We flew and I was holding the yoke,” Maeda recalls. “That was my first experience flying — it was a 30- to 40-minute discovery flight.”

Maeda ended up being able to pursue his pilot training, which he completed in 2005.

To this day, he says he is grateful to Embry-Riddle. He said the university accepted him as a student, despite his initial struggles with English, and allowed him to follow his dreams.

“One professor told me, ‘You’ve been pursuing an aviation career, and we didn’t want you to stop,’” Maeda says. “I was just amazed how Embry-Riddle did that for me.”

Overcoming Challenges through Aviation

Still, Maeda says there were plenty of times when he almost gave up on his Earthrounder Mission. But when he got bogged down in negativity or worried about failing his mission – his family, particularly his late father – inspired him to keep going.

“My dad passed away four years ago. He had cancer unexpectedly, and when we found out, he only had a month to live,” Maeda says. “He said, ‘I’m counting on you son — you have to make it happen. Everybody is looking for hope and dreams.’”

Then when the pandemic happened, the trip seemed particularly significant, he says.

“Because of this pandemic, everybody has lost hopes and dreams,” Maeda says. “So I hope to inspire others and encourage them to pursue their dreams.”

“I hope to inspire others and encourage them to pursue their dreams.”

— Shinji Maeda (’05)

It was fitting that he flew a Bonanza like the ones he watched flying over him as a child in Japan. The plane’s name, Lucy, also had special meaning.

“I had a dog named Lucy who had bone cancer and had to have a leg amputated,” Maeda says. “She was a three-legged dog, but active and happy. So my wife suggested the name, and on the dashboard there is a dog bobble-head statue. So I had Lucy to support me during my trip.”

One of his favorite parts of the trip was flying from Goose Bay, Canada, to Greenland and Iceland, accompanied by his longtime friend and mentor Adrian Eichhorn.

“It is just breathtaking,” Maeda recalls. “I have never seen that type of scenery, and the air was crystal clear.”

People met and greeted him all over the world, but one of his most special visitors was his mother, who is battling cancer. Due to the pandemic, he could not enter the country, but he was able to see and talk to her through the airport fence.

“That is one of the reasons I flew around the world.” he says. “My mom has been supporting me since Day One.”

Maeda, who is also a flight instructor, says he does not have plans for another flight around the world, but he wants to continue to encourage and help others challenge themselves and reach for their dreams.

“Always aviate — it is our life,” says Maeda. “If you try to move forward, things will happen. That is the attitude you need to have toward life.”