As the James Webb Space Telescope shares the clearest images of the universe ever seen on Earth, the hundreds of engineers who constructed the spacecraft are finally seeing tangible results after years of laboring over complex parts that allow the 13,000-pound telescope to operate in space.

Embry-Riddle alumna Tasha Graciano (’10) is one of them. For six years, she was a test engineer on the project at Northrop Grumman in Redondo Beach, California, primarily working on the sunshield.

The five-layer sunshield, made of an extremely thin composite material called Kapton, had to be loaded into a capsule, withstand the flight into space and then deploy, protecting the multi-billion-dollar experiment from the sun’s heat and enabling the telescope to successfully operate in near-infrared at a mind-bogglingly cold temperature of 50 degrees Kelvin, or about -370 degrees Fahrenheit.

Graciano was a test engineer for the 107 membrane release devices, known as MRDs, which function like pins keeping the diamond-shaped sunshield layers securely folded in place during launch and flight and releasing them once an electrical signal is sent from Mission Control.

“We always said that the MRDs were the gift that kept giving because something always just happened with that – like nothing ever went according to plan,” she said.

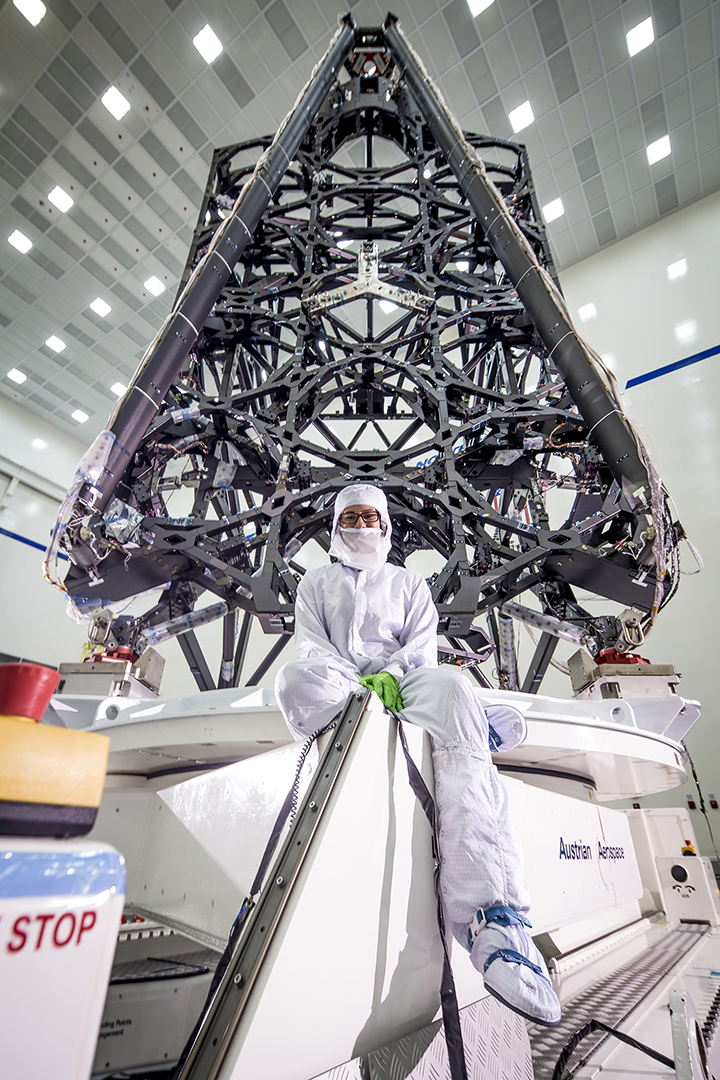

As a test engineer, Graciano received the design engineers’ plans and created instructions for technicians to build the spacecraft. Graciano and a systems engineer would troubleshoot as a technician performed a task – all wearing their white full-body suits in a clean room. And then the various systems faced multiple iterations until the final optimal version.

“I think every day was memorable on Webb,” Graciano said. “But when we did deployments, when you actually get to see what you’ve been working on work and do what it’s supposed to do, or you see the wings of the telescope deploying – it becomes real.”

Graciano became something of a roving test engineer in addition to testing the MRDs. Though she most often worked on the sunshield, she also worked on the bus, the part of the craft below the sunshield that operates the telescope.

“At one phase, I was responsible for maybe four operations for different subsystems getting installed at the same time on critical paths, so I had to know a lot,” she said. “Whenever something came up that they wanted to change, or they needed to install, they were like, ‘Can you take this task? Can you write the procedure to install this in a month?’ So I kind of became that person.”

As we know now, the sunshield opened after launch and is keeping the James Webb Space Telescope within the extreme cold temperature range needed to create images that even in a few short weeks are making good on the promise to transform what we know about our cosmic past and the future of space exploration.

“You’re just like, ‘That’s really in space. And I had my hands on it.’”

– Tasha Graciano (’10)

Before the telescope launched on an Ariane 5 rocket from French Guiana on Dec. 25, 2021, Graciano was there removing temporary hardware after the sea voyage from California and completing final installations.

Graciano watched the launch on TV at home. It was interesting. But the magnitude of the endeavor didn’t set in yet.

When the first sharp, textured pictures from the telescope appeared online, it was a different story.

“You’re just like, ‘That’s really in space. And I had my hands on it,’” she said.

“Never would I think that I would be involved in something that had this much light on it. That had this much importance for the science community.”

At Embry-Riddle, Graciano studied space physics as an undergraduate in Daytona Beach, Florida. As the Milwaukee, Wisconsin, native became an engineer, she realized she wanted to stay in aerospace, but she didn’t want to work from behind a telescope lens.

“I realized I really enjoyed the taking apart and actually putting stuff together and kind of troubleshooting that,” she said. “That’s why I like integration and testing because you get to be with the hardware in person.”

Before she interned at Northrop Grumman in 2015, she didn’t know anything about the James Webb Space Telescope. When they handed her a wrench to work on a component, she was sold. In 2016, she got this job working on the telescope.

Aerospace is definitely for her. After Webb launched, she was promoted and has a leadership role on another project at Northrop Grumman. She wants to stay in the space sector.

At work, a colleague has the picture of the Carina Nebula on his computer monitors. That’s her favorite photo so far.

“From an astronomer’s point of view, it’s going to change the way that you understand the composition of stars, of galaxies, of basically the universe because we’re going back to the beginning of everything,” Graciano said.

“It’s definitely an incredible task that we’ve been able to achieve, and it only opens up the door for bigger and better opportunities to come our way. Since we know we can make it work with this, the opportunities are endless.”