Museum director Chris Browne (’19) has a secret favorite among the aerospace artifacts and icons at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

“Every artifact tells a human story,” says Browne. One in particular is part of his own story.

The Wright Flyer, Jackie Cochran’s T-38A, and Lucasfilm’s X-wing Starfighter are must-sees for any true aviation geek visiting new galleries at the main museum on the National Mall. However, Browne has a personal connection to a Grumman F-14 Tomcat on display at the Museum’s other location – the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center near Dulles Airport in Virginia.

“You love all your children equally, but the F-14 at the Udvar-Hazy Center is one that I flew. It’s in my logbook, which makes it all the more personal.”

The west wing of the flagship building on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., re-opens Oct. 14. Browne is leading a seven-year renovation program begun in 2018. He oversees the work to reimagine the museum’s galleries with eight new and renovated exhibits and a planetarium opening in this first wave. Forty percent of the artifacts in these displays are in the building for the first time and the galleries integrate more digital and interactive experiences.

Ultimately, the overall upgrade will redesign all 23 exhibitions and renovation spaces.

Despite Browne’s son teasing him that most of the objects in the museum are artifacts and therefore, he must be a relic, his lifelong love of aviation links him to items of more recent vintage, though not so directly as the F-14.

He also has a wish list that includes the F-15, F-16 and YF-17. The museum continues to work with the U.S. Air Force and NASA to identify airframes and craft that can be acquired or loaned.

From Aircraft Carriers to Airports to Artifacts

Browne has been immersed in the museum world for just five years and it was far from a direct path to this dream job. He spent his high school summers in the Canadian arctic around float planes and earned his private license in 1978 at Dartmouth College, where he joined the flying club.

Extremes appealed to him and he considered life as a bush pilot or Navy fighter pilot. He chose seven years in the U.S. Navy, deployed on a carrier, flying F-14s, and on one harrowing occasion, ejected from a burning Tomcat. Long deployments at sea were hard on family life, so he decided to continue his pursuit of “all things aviation” and began a career in airport management.

“I always liked operational spaces and was drawn to airports as hubs of activity,” he says. His timing was perfect. When Reagan National Airport was transitioning from operation by the federal government, he was hired by the newly created Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority, which took over operation of National and Dulles Airports. He became the airport manager in 1997.

This marked an intense period, with challenges ranging from addressing the uncertainties that came with Y2K to operating during the Sept. 11 attacks to managing the large capital program that included building out a new terminal.

“You love all your children equally, but the F-14 at the Udvar-Hazy Center is one that I flew. It’s in my logbook, which makes it all the more personal.”

— Chris Browne (’19), director, Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum

In 2005, he moved to managing Washington Dulles International Airport, which was larger in passenger numbers and physical size, as it was expanding terminals and introducing its Metrorail system. He found his 30-year career with airports hectic, chaotic and rewarding. He wanted to stay on top of emerging technology as well as best practices, so he earned a Master’s degree from Embry-Riddle Worldwide. He was aware of the school from his years in the Navy.

“Embry-Riddle is always a standout in the aviation space and the brand and reputation has grown considerably in recent decades. I knew if I wanted to advance my career, I needed education and experience from a notable name that helped ‘professionalize’ the industry.”

He was about to put that degree to work for an airport engineering firm in Richmond when a friend called him about a posting in USA Jobs: deputy director for an aerospace museum. He realized he would be working for director Jack Dailey, a former Marine Corps general whom he knew from his airport operations days.

Browne had only three days to complete the complicated application. Not long after, he explained to the engineering company he was turning down that he was taking a new position that involved a massive capital campaign – tearing the museum down to steel and rebuilding, vacating artifacts, creating exhibits, securing new items and reinvigorating the storytelling, because, “it all starts with story.”

He was promoted to serve as the John and Adrienne Mars Director of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in 2022.

“It has been a large public and private partnership, with taxpayers funding about $729 million for the project. Philanthropy will pay for the build-out of all the galleries. Donors have provided about $250 million of our $275 million goal.”

The Smithsonian will also be home to a new science, technology, engineering, arts and mathematics (STEAM) educational center, privately funded with a gift of $200 million from Jeff Bezos.

As demanding as the nuts and bolts of construction and restoration can be, context is a driving force for Browne. It is important for him to share stories, from pioneers of aviation to space exploration, in a way that encourages people to see themselves. He uses the Apollo missions showcased in Destination Moon as an example.

Welcoming People into the Story

“Recently, President Biden used the term ‘moonshot’ to discuss his cancer research efforts, but people who were not alive during Apollo may not realize how audacious this idea was. Our Destination Moon gallery walks them through what we thought the Moon looked like in the ’50s, toys that inspired the astronauts as children, and milestones of Mercury and Gemini missions. You experience the whole timeline.”

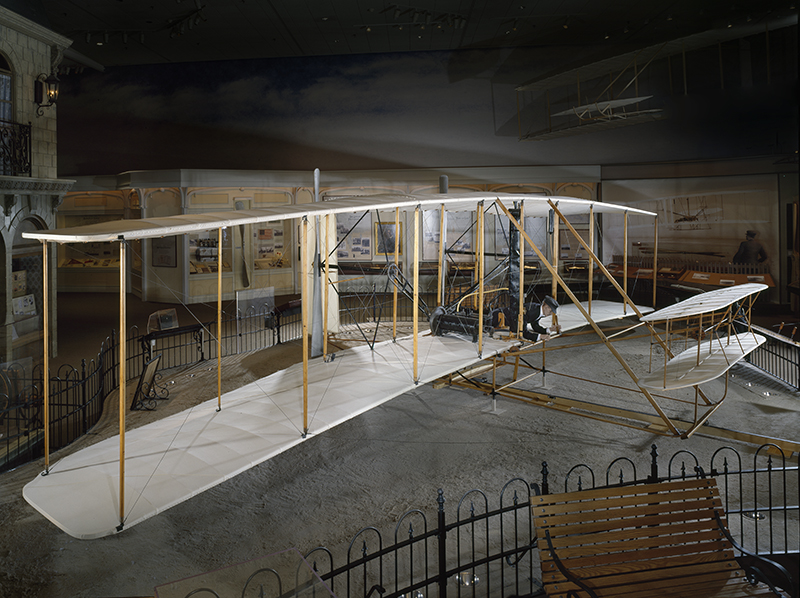

Browne points out that we do not have to go back more than 50 years to appreciate the relevance of earlier innovation. “One of the interesting things about the Wright Brothers is that they developed engineering principles used today at Northrop, Airbus and Boeing.”

He feels engaging throughlines will help visitors see themselves in the stories and discover relatable pioneers who were once ignored.

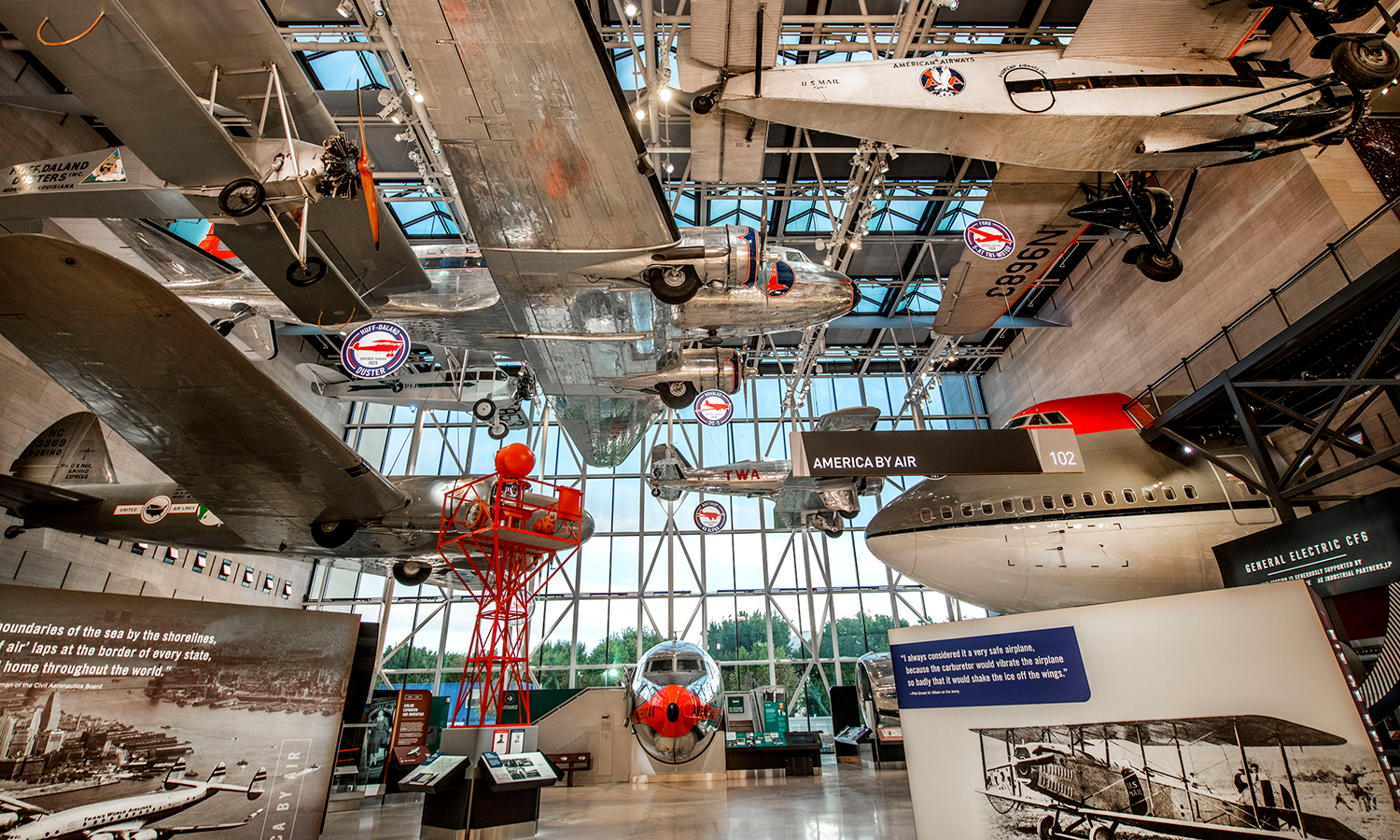

“If you walked through America by Air, a gallery that was largely unchanged from when it opened in 1976 that tells the story of commercial aviation, a young girl contemplating a career with the airlines would only see women represented as stewardesses. Now there are pilots and engineers and mechanics included.”

A compelling new story is that of Neal Loving, the first African-American and double amputee certified by the Air Races Association. One of Loving’s home-built aircraft is on display for the first time at the D.C. museum. Loving designed it with folded wings so he could trailer it behind a car and drive to a field to launch.

“The aircraft is one of the first that people see when they come in. It is positioned in front of a large mural painted by Edward Sloan so it seems to fly out into airspace,” Browne says.

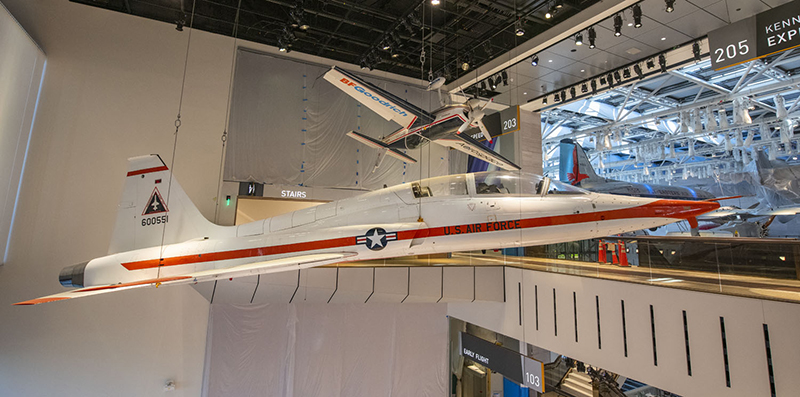

Jackie Cochran’s T-38A Talon sits at the opposite end of the display area. Cochran was the first woman to exceed the speed of sound. At her death in 1980, she had set more speed and altitude world records than any man alive.

“Supersonic flight isn’t the sole domain of people like Chuck Yeager. We have the Bell X-1 (‘Glamorous Glennis’) on display (temporarily at the Udvar-Hazy Center before it will return to the D.C. building), but also displaying Cochran’s T-38 delivers a more balanced story.”

Unlike some museums, National Air and Space does not focus solely on the past. The museum integrates past, present and future, the personal and the technological. It also highlights how the past can illuminate the future.

“We are living in a golden age of space flight, just as there was once a golden age of aviation. You can see the parallels in a new gallery, We All Fly, which tells the story of general aviation from a broad perspective. There are so many similarities between how aviation evolved and how private and commercial spaceflight is evolving.”

In interpreting his own timeline and story, Browne says he has no recipe for success to recommend.

“I can’t tell an Embry-Riddle student or graduate: This is what you need to do. However, I was prepared when opportunities presented themselves thanks to wonderful mentors and the fact that I surrounded myself with people who encouraged my drive and passion.”

Today he is making the most of a unique opportunity to spark that passion in others.