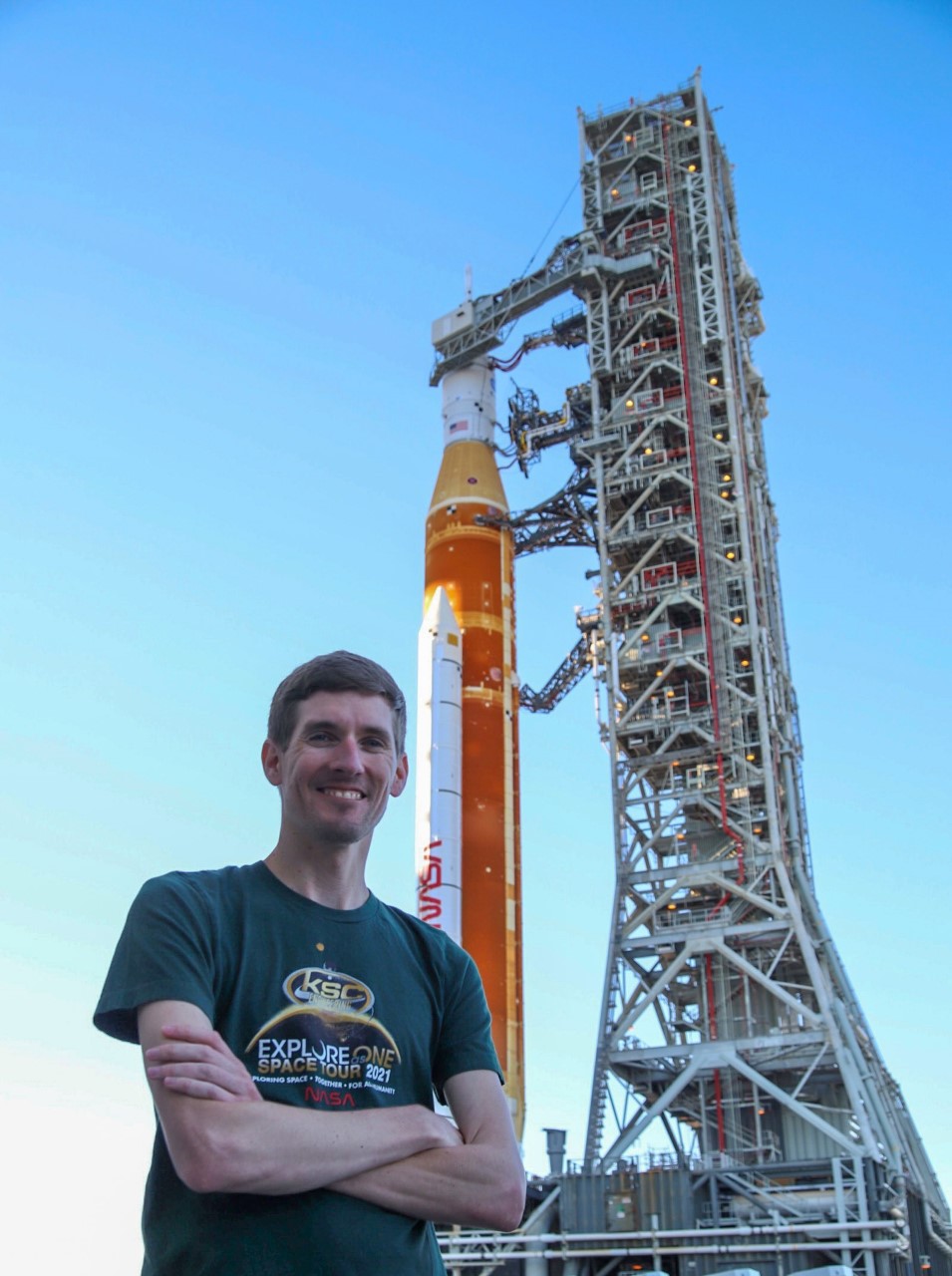

When America gets its first good look at the Artemis 1 Moon mission, Scott Cieslak (’09) will be watching from the firing room in the launch control center at Kennedy Space Center, eyes fixed on the umbilical arms connecting the Space Launch System rocket and mobile launcher. This crucial wet dress rehearsal simulates all the steps of a launch without actual ignition.

The umbilicals will deliver power, communications, coolant and fuel to the rocket and the Orion spacecraft on the launch pad. At ignition and liftoff, after the umbilicals retract and disconnect, just as they were designed to, Cieslak will breathe a sigh of relief and mark one of the proudest days of his life.

“If working out here and being around rockets doesn’t excite you…”

He doesn’t have to finish the sentence. Scott Cieslak can’t imagine a more motivating job. Since 2019, he has played a pivotal role in authoring, reviewing and executing the arms and umbilical mate procedures as an operations engineer in NASA’s Launch Accessories Engineering Branch.

Growing up with car buffs, Cieslak often visited the Daytona International Speedway. As a sophomore, he added a side trip to the Embry-Riddle campus, and he liked the atmosphere. Living in Maryland, he was familiar with Goddard Space Flight Center, and he thought his strong math skills could lead to a career as a mechanical engineer. Learning more about Embry-Riddle refined that ambition to aerospace engineering.

Engineering 101 got him into the aerospace mindset, but beyond that, he remembers Professor James Ladesic’s emphasis on safety and ethics. Cieslak says, “Part of that course that has carried me through my career, especially what we do here, is the idea that engineers must be strong ethically and not buckle to pressure to do something that may not be right from an engineering perspective.”

Cieslak also credits Dr. Eric Perrell, his senior design professor, as a lasting influence. Dr. Perrell guided the first Embry-Riddle team to compete in the NASA Student Launch, a research-based rocket-propulsion challenge. The yearlong project required the team to “figure out what your rocket’s going to be, your payload, what it’s going to do for science and then build the concept.” They also raised funding.

After design reviews with volunteers at NASA and Marshall Space Flight Center, the team launched their 10-foot rocket at Marshall. “That was a cool way to cap my career as a student.”

While working on his aerospace engineering degree, Cieslak spent two semesters as a co-op student working for a shuttle contractor at Kennedy Space Center. “I was an operations engineer for the umbilicals for the shuttle. That was an introduction to working with a launch vehicle and real hardware and understanding to get a mission off the ground and bring it back safely, process it and turn around and support astronauts.”

“If working out here and being around rockets doesn’t excite you…”

— SCott Cieslak (’09)

Upon graduation, he went to work for the shuttle program for two years. He left Florida for an aerospace company in North Carolina but returned to NASA in 2015 as a contractor and became an employee in 2019.

The umbilicals’ complexity demands a range of engineering skills, from mechanical systems to electrical, to cryogenics and pneumatics. Cieslak traces his focus on mechanical engineering back to his random co-op assignment. “I happened to be assigned with an umbilical person and thought, “Hey, this stuff’s pretty cool.”

He still thinks it’s pretty cool, especially with Artemis in the spotlight. “The umbilicals are the last things to touch the vehicle before it goes into space, so their importance to the Artemis program can’t be overstated.”

And each time they let the vehicle go, he says, they are releasing something special: the potential for human beings to go farther than ever before. “Ultimately, we leave the comfort of our space station module. Live on another planet. Take that next step on to Mars. The technology spin-offs are going to be incredible.”