When the MacArthur Foundation named its world-changing Fellows for 2022, Embry-Riddle alumnus Moriba Jah’s name was on that list. Often called the MacArthur “genius grant,” the no-strings-attached $800,000 award is for those showing exceptional creativity who are likely to make advances based on their track record.

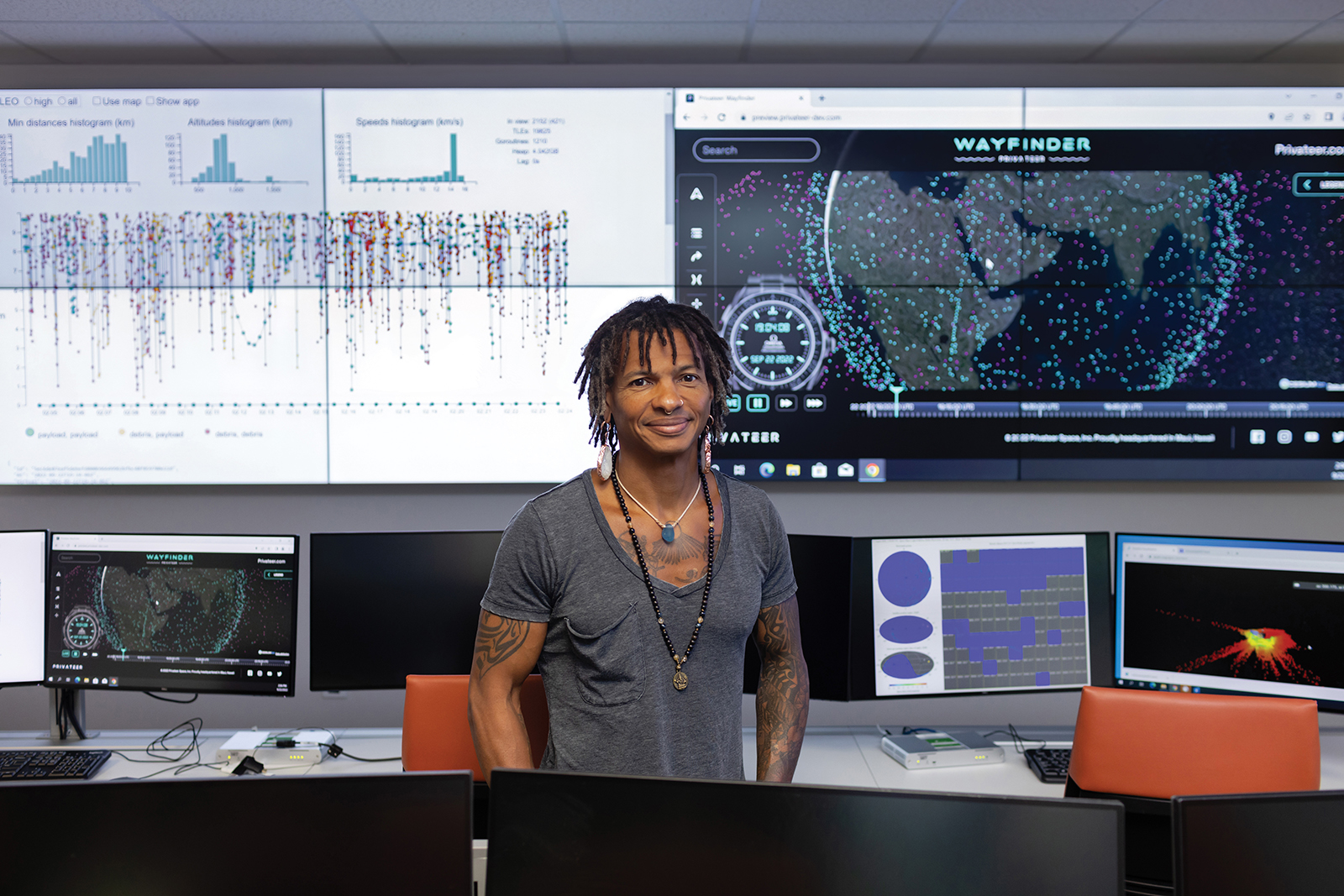

Jah (’99), an astrodynamicist at the University of Texas at Austin, fulfills those requirements and more. In the last three years alone, he’s been named to prestigious boards and fellowships and co-founded Privateer with Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak and tech innovator Alex Fielding. The company’s mission is to create data infrastructure to help sustainably grow the space economy. In 2022, he was named a member of the Federal Aviation Administration Commercial Space Transportation Advisory Committee, a TED Fellow and a Fellow of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

His career trajectory after serving in the U.S. Air Force has hit the high points of aerospace, from being a spacecraft navigation engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, to leading the Advanced Sciences and Technology Research Institute for Astronautics at the Air Force Research Lab.

With all of those achievements, he has a goal that is literally beyond the world’s boundaries: To ensure a sustainable, inclusive future for the space economy that is currently threatened by the proliferation and decaying orbits of space junk. Of the 27,000-plus objects the size of a softball or larger being tracked in Earth’s orbit, 4,000 are active satellites and spacecraft. The rest is, as he says, “garbage.” A key part of that vision is here on Earth, he says, in how we approach the world and whether we heed what Mother Nature has to say.

Here’s a conversation with Jah, edited for length and clarity.

What do you most want to communicate when you speak publicly?

The main thing that I want people to be able to do is empathize with the problem. So my first call to action is to try to recruit empathy from people. How can I present the problem in such a way that they can connect with it, that they can understand it, that they can project themselves into this perspective and see it as their own problem?

One of the main risks with space junk is harm to human life, whether that’s in space or on Earth. Can you talk a little bit more about this?

More and more people are being launched into space. And none of those capsules or space vehicles are shielded from being hit by something traveling at a very fast speed. There’s a very real possibility of a loss of human life in space. In terms of people on Earth, things are re-entering the atmosphere all the time, and very large things are left to re-enter on their own to leave Mother Nature to deal with it. Some of these things could survive re-entry and have, like a Chinese rocket body the size of a school bus re-entering with the possibility of it hitting a populated area. [Note: One of the most recent occurrences was a rocket booster that re-entered in July over the Indian Ocean.]

How can loss of orbits impact the space economy?

We put satellites in very specific orbits, or orbital highways as I like to call them, and these are becoming more congested, because when things die in orbit, they don’t just come back, they stay up there for a very long time, traveling at very high speeds. So you have a bunch of dead objects that are now traveling the same lanes as satellites providing critical services and capabilities that are not protected from getting schwacked with a piece of space garbage. Losing the ability to use these orbits means us losing a very critical service and capability provided by satellites. And I would say that humanity gets to know more about itself and the Earth because of these robots in the sky that we call satellites.

And this is also happening when we’re sending more and more satellites and spacecraft into space?

Yeah, basically five years ago, we’d have maybe 12 launches a year and now we’re having more than 12 satellites launch every week.

I was looking at Wayfinder, your open-sourced software showing space junk orbiting Earth, and it’s really interesting. Tell me more about how it works.

I’ll put it this way: It’s a tool for anybody, even people who are operating satellites, because you can click on an object, and you can download its position and velocity predicted over some time horizon. To a great extent it’s trying to get humanity enrolled in this vision of space environmentalism. The dots don’t represent the size of the object by any means, just the locations of these things.

One of the things that Privateer wants to do is make space more transparent. Learning what’s up there, who it belongs to and what it’s doing makes space more predictable. How do we develop a body of evidence that people can use to keep themselves safe and also to hold people accountable for their behaviors in space?

Can you describe some of the difficulties in doing that?

The thing is, if you want to know something, you have to measure it. If you want to understand something, you have to predict it. We don’t have measurements of everything in space, just collect samples here and there. And so we have to infer things statistically. Anytime that we try to draw these conclusions, they are mired in uncertainty. Even when you go to Wayfinder, those objects aren’t exactly there. Those are just predictions. Some predictions are going to be way off. And so there’s a lack of accuracy and precision, because we don’t have ubiquitous sensors and data measuring everything all the time. We basically have to play Sherlock Holmes and piece things together with different measurements from radars and telescopes. Then we have opinions from other people about where stuff is, and sometimes those opinions are in great conflict with each other. So that’s a challenge there as well.

What does the data tell you?

Based on the way that we’re behaving, we’re in trouble unless we change. I think the quickest way to get change is governments need to take action. And for me, the quickest way for governments to take action is when people levy this on their elected officials, which means having to get people involved. If humanity doesn’t get involved in a problem, it doesn’t get solved.

“You have a bunch of dead objects that are now traveling the same lanes as satellites providing critical services and capabilities that are not protected from getting schwacked with a piece of space garbage.”

— Moriba Jah (’99)

You mentioned government. Who do you think needs to be a part of this conversation?

The first people I would invite would be the Indigenous people. They’ve been thriving in very harsh conditions for tens of thousands of years, some of them successfully. How did you do it? How did you have a successful conversation with the environment? A lot of these indigenous people every day, they’re in an existential crisis, and they believe that they live their lives that way. I think most people in our Western civilization don’t live as if we’re in an existential crisis. But when you believe yourself to be in an existential crisis, you start behaving a bit differently. Maybe I should, for my own sense of preserving my own self, start behaving differently because I want to be around for a while.

I saw that you had also helped to work on the World Economic Forum Space Sustainability Rating.

It’s trying to incentivize people to behave in sustainable ways. And the thing is, consumers can choose to support products of companies that have some evidence that they behave sustainably. As a runner, I can choose to buy Nike shoes or not, depending on what I believe their sustainable practices are. If a company is providing internet but at the same time, there’s evidence that they don’t care about the environment, then maybe I don’t subscribe to their internet service. At the end of the day, people have some agency in who they support or not with their pocketbooks. What I’d like to do is motivate more people to say, ‘Hey, before you spend your money, maybe I can make it easier for you to see evidence of sustainable behavior or not. And then it’s up to you to decide based on your own set of internal values what you’d like to contribute your money towards.’

So what are some of your goals in trying to help people solve this problem?

There’s two core beliefs underpinning Privateer. One is that all things are interconnected. And when you believe that all things are interconnected, then any harm to anything is really an act of self-harm, because eventually it comes back to you in one way or another. Believing that all things are interconnected means that you don’t believe that there’s such a thing as true independence. Like we’re all somehow interdependent on each other. Things that are happening on the other side of the planet, while we may not experience them today, eventually we will. So independence is really something that people believe in if they have not looked far enough, if they have not looked long enough, and if they have not looked deep enough, but if you do those things, then you see evidence of this interconnectedness.

Another belief is that we are stewards of the planet. And I think, by and large, this has been forgotten or neglected by many people. When you embrace stewardship as if your life depends on it, then the outcome tends to be much different. And it means having a successful conversation with your environment. This is deeply rooted in something called TEK, Traditional Ecological Knowledge. People say that they’re in the tech industry. I’m also in tech but I’m into ancient tech and into TEK, which is this knowledge that Indigenous people have had premised on interconnectedness and embracing stewardship.

You’re dealing with the mess that we have now and trying to prevent future pollution. What are some ways that that can be done?

Just like here on Earth we try to minimize single-use plastics and try to emphasize reusability and recyclability. The same thing for space. We need to emphasize reusability and recyclability of rockets and satellites.

It seems like the public’s awareness isn’t quite where it could be.

It’s definitely slow. But most of the awareness is going to come from things that have nothing to do with space. Mostly the awareness is going to come from news outlets like CNN that basically are more mainstream to humanity. Most of the awareness is going to come from working with artists, making music, creating films. That’s where most of the awareness is going to come from. So contrary to the popular belief of many scientists and engineers, awareness doesn’t come from presenting more scientific and technical conferences. It comes from making this mainstream by connecting to artists and things that really connect to people.

What are some things that you think would signal positive change in the next 10 years?

For me a signal of positive changes is seeing evidence that people actually believe in this interconnectedness. People are behaving more like stewards instead of owners of things. Making decisions in a positive way, allowing Mother Nature to give you feedback of the unintended consequences of your actions before you keep on making decisions. That would be a signal of positive change and having an inclusive dialogue saying, ‘Hey, we need to invite everybody to the table and give them decision-making powers,’ so to speak. So that the way that we use space is something that everybody gets to weigh in on, not just the few.

When you look back at the last five to 10 years in your career, what have you done where you think, ‘Yes, this is how I made a difference?’

This idea of space environmentalism is something that I coined. Just months ago, I saw somebody, on their business card their title was space environmentalist. I love it. That means that there’s something that I’m doing or saying that’s reaching people.